Note: "spoilers" are abundant below. Most of what's mentioned is older than a few years.

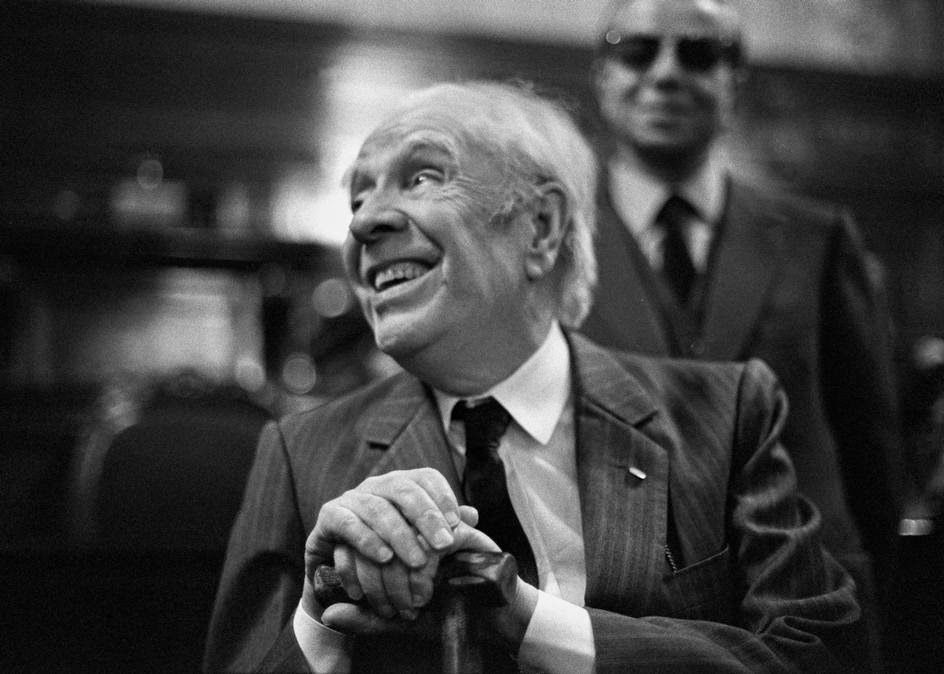

Earlier in the last century, renowned short story writer Jorge Luis Borges called for an increase in epic stories of heroes, in the vane of classic poetic epics:

In a way, people are hungering and thirsting for epic. I feel that epic is one of the things that men need. Of all places (and this may come as a kind of anticlimax, but the fact is there), it has been Hollywood that has furnished epic to the world. All over the globe, when people see a Western—beholding the mythology of a rider, and the desert, and justice, and the sheriff, and the shooting, and so on—I think they get the epic feeling from it, whether they know it or not. After all, knowing the thing is not important.

Borges criticized the state of the novel at that time, due to its lack of heroic aspects and happy endings:

Well, nowadays if an adventure is attempted, we know that it will end in failure. When we read—I think of an example I admire—The Aspern Papers we know that the papers will never be found. When we read Franz Kafka’s The Castle, we know that the man will never get inside the castle. That is to say, we cannot really believe in happiness and in success. And this may be one of the poverties of our time.

At face value, Borges's call was answered, and intensely! We are in a time where hero stories, following a similar configuration, seem to be the main mode for (at least American) film and TV.

A few years ago, I underwent an abrupt shift in my attitude about the modern manifestation of these types of stories. As far as I can remember, a hero gets a call to adventure, some trials occur, there's a happily ever-after. Few principal characters suffer significant losses in disney films. Heroes "overcame odds". I'd taken these as good and whole, indicative of the experience of most people in the world.

But at some point, finding myself in a fairly mundane life, having had no call to adventure, and seeing most others without, I started to feel this narrative was a lie. It didn't resonate with experience.

I've heard that empathy and awareness of others often increases with age. All it takes is a bit of a look around to realize that retail service worker is probably not living his or her dream. The young person who suffered the loss of a limb won't be climbing a summit. The kid who died in a car accident won't be finding a soul-mate.

It was a realization and a feeling that the most widely-available stories are sold as if they can enrich and inspire, when they may be more like a dream, a hollow fantasy, a drug.

Eric Molinsky, host of the podcast "Imaginary Worlds" takes the same line of skepticism in the episode "The Hero's Journey Endgame". As he asks:

As we reach a saturation point of sci-fi fantasy and superhero franchises, has The Hero’s Journey outstayed its welcome?

And Eric's interviewee, culture critic Abraham Reisman seems to have a pretty clear answer, talking about the "monomyth" (a.k.a. "the hero's journey"):

I would say the harm is the mono-myth is a machine designed intentionally or not to make you a narcissist. The mono-myth is all about how a singular entity has the entire universe laid out for him or her – of course usually him -- and everything that happens is only relevant in so far as it affects him. That's a mindset that the older I get the more I think is the cause of a lot of problems in the world it leads to this sense of avarice and covetousness and I just think it's not healthy to constantly be exposed to Heroes Journey stories.

Reisman puts its well: contemporary hero stories are focused on the individual protagonist, and are packaged in a way that each of us as individuals are meant to map ourselves onto the hero. Iron Man is a natural-born tech genius who uses tremendous wealth and power to save those he deems worthy. We are meant to think: "I too could be a wealthy natural-born genius who helps those I choose."

We need not even look narrowly at superhero or fantasy films (though prominent examples outside of those categories are getting harder to find)

Let's look at a top-grossing, non-disney, non-superhero film. 2018's Mission Impossible: Fallout followed a similar narcissistic path. The principal character ostensibly faces challenges (mainly being chased), but they're illusory challenges. Some fast running, professional motorcycle-driving, or skilled helicopter-piloting will always resolve the conflict, and usually there are no permanent costs or injuries to such actions. We're meant to insert ourselves as the naturally-skilled mission operative, for whom danger is never real. Because protagonists don't die in the modern hero's journey, where solutions to problems are inevitable.

I'm left wondering nowadays: where are the secret agents who died? Where are the stories about good guys with amputated legs, who aren't relegated to sidekick or support team? How about the ones who never made it to boot camp because of poverty, intellectual disability, or a bad case of vertigo?

You and I will encounter many folks who don't agree the ubiquity of hero narratives with happy endings is a problem. They might say things like "Who cares? I know it's fake." or "I get enough bad endings in my real life." or "I'm looking to escape the real world for a bit, what's wrong with that?"

Well, of course we know fiction is fake in that it didn't actually happen. From my own experience (and I'd wager the experience of many, especially young people), we still have some expectation that it will be representative. You can hear it in the meme that 'art is the lie that tells the truth'. You can see it when people refer to characters who never existed, or quotations never uttered, as inspirations. Perhaps the most notable being Sherlock Holmes. You can find references to surveys where majority of respondents believe A.C. Doyle's famous fictional detective is a real person.

To the point about escapism, I say we have nowhere near a shortage of that. And I'm also skeptical of the variety that seeks to avoid, rather than fix the issues being escaped. The latter type of escape summarized by this from Ursula K. Le Guin (and misattributed to Tolkein):

If a soldier is imprisoned by the enemy, don’t we consider it his duty to escape? The moneylenders, the knownothings, the authoritarians have us all in prison; if we value the freedom of the mind and soul, if we’re partisans of liberty, then it’s our plain duty to escape, and to take as many people with us as we can.

Neil Gaiman wrote something similar, in "The View from the Cheap Seats"

If you were trapped in an impossible situation, in an unpleasant place, with people who meant you ill, and someone offered you a temporary escape, why wouldn’t you take it? And escapist fiction is just that: fiction that opens a door, shows the sunlight outside, gives you a place to go where you are in control, are with people you want to be with (and books are real places, make no mistake about that); and more importantly, during your escape, books can also give you knowledge about the world and your predicament, give you weapons, give you armor: real things you can take back into your prison. Skills and knowledge and tools you can use to escape for real.

The" tool" that I have seen referenced recently, with the most potential empirical support, is empathy, or "EQ".

We will ignore for a moment that there is nuance in distinguishing "genre" fiction and "literary" fiction when it comes to clinical studies about fiction and empathy. Supposing that empathy is indeed a chief "tool"[1] to be taken from stories: hero narratives, the modern kind, don't seem to have much time for it. Not so long as they're more occupied with associating you or I to the character saving people than character being saved. Or more occupied tying us to the character getting the girl than to the character selling empanadas nearby to pay a parent's hospital bill.

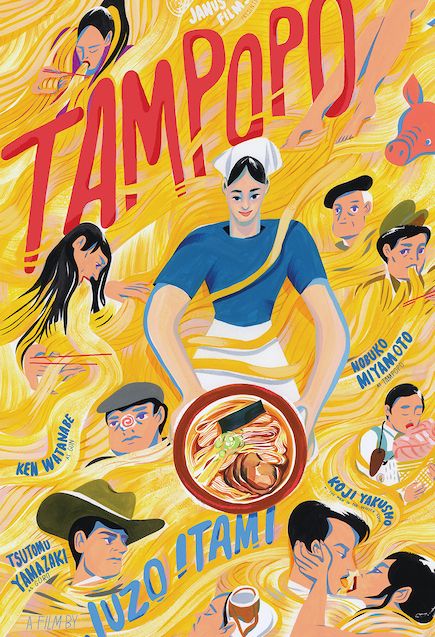

A viewer might object "But the empanada saleswoman's story is boring!" No it isn't. For proof, check out "Tampopo", a great film about a Japanese family running a ramen shop.

Let's suppose for a moment we lived in a world where storytellers with power, influence, and money saw that whatever sells best or has the best engagement often isn't actually what's best for the customer. What sells best is often not even what the customer wants, ultimately. Wanting cocaine, another run at the slot machine, another giant cup of coca-cola are one kind of want. They're different than wanting to make enough money to feed your family, to play cards with friends, or to grow as a human.

We don't even have to go so far in our hypothetical. There are many story types or storytelling techniques that could sell (or have sold!) well. I'll suggest a few antidotes to contemporary hero's journey.

More Tragedy.

As said before, people will argue they don't want to spend yet more of their time to get a reminder that things don't always work out. I'll counter: if you can spend eight hours in an office, and go home and watch a few hours of "classic" television show "The Office” (on your seventh go-round), you could probably spare a bit here-and- there in your story consumption for something like Zvyagintsev's "Loveless". That's a film criticizing the disintegration of social and family ties in contemporary Russia. It culminates in a child's death because of his parents' neglect.

I'm so accustomed to that type of miraculous ending that I sat waiting for a reveal that the child had lived, even as the credits rolled. But unlike for young Peter Parker and other heroes in the Marvel films, death is not a transient state in Loveless. It serves as a reminder when things are bad, they could be a lot worse. But more, a tragedy is a way to dramatically offset hero stories, and perhaps bring our sensibilities and expectations to something more neutral.

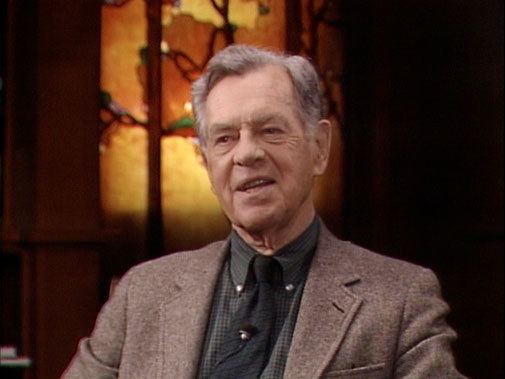

George Lucas and Star Wars are cited as the turning point that led to the dominance of hero narrative as it is today. Lucas was heavily influenced by mythologist Joseph Campbell. But when Campbell was trying to proclaim the value of the fairy-tale ending, he understood the value of tragedy:

“This death to the logic and the emotional commitments of our chance moment in the world of space and time, this recognition of, and shift of our emphasis to, the universal life that throbs and celebrates its victory in the very kiss of our own annihilation, this amorfati, “love of fate,” love of the fate that is inevitably death, constitutes the experience of the tragic art: therein the joy of it, the redeeming ecstasy"

And, like Borges, he spoke from a time he considered almost devoid of happy endings. In the late 1940s:

“Modern literature is devoted, in great measure, to a courageous, open-eyed observation of the sickeningly broken figurations that abound before us, around us, and within."

For us: modern media is devoted to happy ending.

Campbell thought that stories with happy endings, the comedies, ought to complement tragedies:

“The happy ending of the fairy tale, the myth, and the divine comedy of the soul, is to be read, not as a contradiction, but as a transcendence of the universal tragedy of man. The objective world remains what it was, but, because of a shift of emphasis within the subject, is beheld as though transformed. Where formerly life and death contended, now enduring being is made manifest—as indifferent to the accidents of time as water boiling in a pot is to the destiny of a bubble, or as the cosmos to the appearance and disappearance of a galaxy of stars. Tragedy is the shattering of the forms and of our attachment to the forms; comedy, the wild and careless, inexhaustible joy of life invincible. Thus the two are the terms of a single mythological theme and experience which includes them both and which they bound: the down-going and the up-coming (kathodos and anodos), which together constitute the totality of the revelation that is life, and which the individual must know and love if he is to be purged (katharsis=purgatorio) of the contagion of sin (disobedience to the divine will) and death (identification with the mortal form).”

Finally, a tragedy may be most ripe for EQ, for empathy. If we see mostly characters with broken lives and plans, we may begin to feel more that we're not so unlike them, rather than fantasizing about how our prince or princess will come.

Heist

Possibly because of recent iterations of popular heist films (namely the Steven Soderbergh "Ocean's" series) we rightly see heists as simplistic and laden with tropes, ripe for parody. But the idea that heists are mainly about twists is a recent one. At core, heists are about a group of people coming together to take a bit of power away from the powerful, or to accomplish a common goal. IE "The Job".

It's hard for a heist to have a hero in the same sense as a hero-narrative, because each of the crew members needs to play his or her part for the job to go well. By necessity, heist stories are about interactions and relations within the group. Not incidentally, that's how things actually go in our lives.

Too, it's hard for a heist story to have a hero in the usual sense because the characters in the group are morally ambiguous (also how things actually go). For that same reason, the "happy ending " for the group usually doesn't come, at least not in the way they expect.

For example, the finale of the original "Italian Job" is a literal cliffhanger. The crew have successfully stolen the money, and loaded it into a van which they manage to drive partway over a cliff edge.

In "Le Cercle Rouge", the job is nearly a success when several of the main characters are shot and killed.

In "Widows" the job goes well, but the job's organizer has lost an intimate relationship that meant more to her than any sum of money.

Broadly, a heist is a story where an often under-resourced group takes on the powerful or unjust, sometimes at great cost and sometimes bringing a boon back to their community. These are the opposite attributes to the contemporary hero story where a resourced individual who is powerful takes on aliens or monsters, sometimes at cost. But more often without cost since we know victory is inevitable for a handsome protagonist.

Epic Focus

There are elements of Borges's and Campbell's discussions that suggest present-day heroic narratives don't actually jive with what they were talking about. For Borges, it was essential that the epic was a poem, a song. It spread as a collection of communal memories and lessons, and often formation of national identity-as with Finland and The Kalevala, or Iceland and the Poetic Edda. Or even America and Whitman's Leaves of Grass. It's a bit hard to imagine that Borges would envision such an unmusical rendering of Norse myth as the original Thor film in the same vane as The Poetic Edda.

Similarly, for Campbell it was about myth: a collection of wisdom and inspiration grown over decades or centuries. The average ancient Frenchman seems unlikely to have imagined himself as Roland the furious, just as the average Irishman was

unlikely to insert himself as Finn McCool. Instead they'd enjoy the tale and perhaps take pride in the adventures of one of their own. They'd pay attention to the reputation and boons the hero brought back, lessons and virtues.

By contrast, Harry potter stories put you behind Harry's eyes, and tell you that you can defeat your enemy because you are the "chosen one"[2]. Regardless of your competence level.

David Sims drew a nice contrast between two types of hero stories in the Atlantic. Iron Man and Speed Racer were released within a week of each other. Iron Man featured an arms dealer using his singular genius to escape poor Middle Eastern people, his replacement of large imprecise weapons with smaller more powerful ones attached to his hands[3], his triumphant return to adoring fans, his unilateral decision to "privatize world peace".

Meanwhile, a recurring theme of Speed Racer was its hero's uncertainty his actions would actually be glorious or even useful. But he world live by his virtues anyway. He would do the best he could, with skills he practiced, to evoke change one place he felt able: on a race track. In other words, "to become the most himself". Not to become "the best". And he did it because he wanted to make things slightly better for his family and friends. That's rather humble elixir.

Iron Man led to a subsequent decade (and counting) of cinema dominance, where focus falls on the hero's prizes (freedom, a new corporate venture, power, a pretty girlfriend, preventing planet-scale destruction).

A focus on the hero's virtues (love of friends, ethical business dealings, comparison to self rather then others), would be prophylactic for the negative effects of the hero-story.

Monsters

A thread runs through the films of Guillermo del Toro and works like Emil Ferris's My favorite thing is Monsters. That thread is that monsters can be good, that beauty is not a proxy for goodness. For Ferris's characters, monsters were a source of hope because they were outcasts. An average isolated or lonely person like you can identify with them. A story of a monster is in some ways the story of that empanada vendor who doesn't get a second look, or the ship mechanic of a star base in Star Wars.

I hesitate here, in that a film like "Shape of Water" subverts a deep trope, where a hero slays a hideous beast. But the del Torian monster seems to be something different than a beast. The latter with its roots in the misunderstood giant brought to life by Frankenstein rather than the fire-breathing avaricious rage of a dragon.

Telling this type of story gets some of the best of both worlds: a fairy story

of the unseen people, with hopeful and fantastic elements.

Protagonist Death

I dislike several things about Game of Thrones, enough that I stopped reading the books and watching the series. But one thing that it does supremely well is to create the impression that characters' actions have dire consequences, or that acts of chance may injure them, just as for you or I. The series is so known for deaths that people have gone to great lengths to make detailed data visualizations of when and how they occur. I'll infer that some of this is because the series's author was inspired by the actual events of ancient English civil wars. Contrary to expectations of hero stories, audiences went wild for this kind of storytelling.

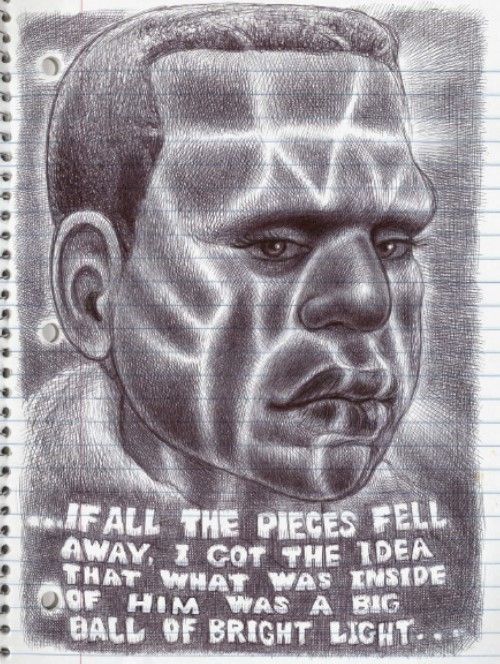

From another angle: Blade Runner 2049 worked so well because it used some sleight-of-mind with the 'chosen one' trope we've come to expect. Its main character, called K, spends most of the film thinking he's a special prophetic human/machine hybrid. Only to discover that this special character was someone he'd met on his quest earlier in the film. At last, he sacrifices his life to reunite that character with her father.

There's no prize for this hero. An audience member is not living vicariously through K as he determines that his soul mate was an illusion, a marketing ploy. Or hears that his visions are fabrications. Or as he lay dying, alone. K's story was not exactly a happy one. He wasn't heroic in the sense we mean: there was no triumph over a world-threatening evil, no staring into a sunset with a trophy in hand. But he was heroic in an old way: he was an exemplar, a model for how to act when the universe is not laid out for you, and you're bombarded by chance events. In some ways, it is a repository of a piece of cultural wisdom.

1Putting aside for the moment the abject strangeness of calling something a deeply human quality, empathy, a "tool" like it cuts wood or sucks dust off surfaces.

2I recognize that ultimately Harry gets a kind of revelation that his protected status is somewhat accidental, but he's still "chosen", just randomly in that case. And part of the accident was that his parents loved him enough that their love granted some protection-with little said about other parents and children who would have been in similar circumstances.

3His company ceases manufacture of missiles, he now instead wears an invincible armor with a kind of energy-blsting hand mounted weapon that has an elaborate targeting system. Notably it is now solely up to Iron Man who deserves violence from these new weapons, the company has no say.